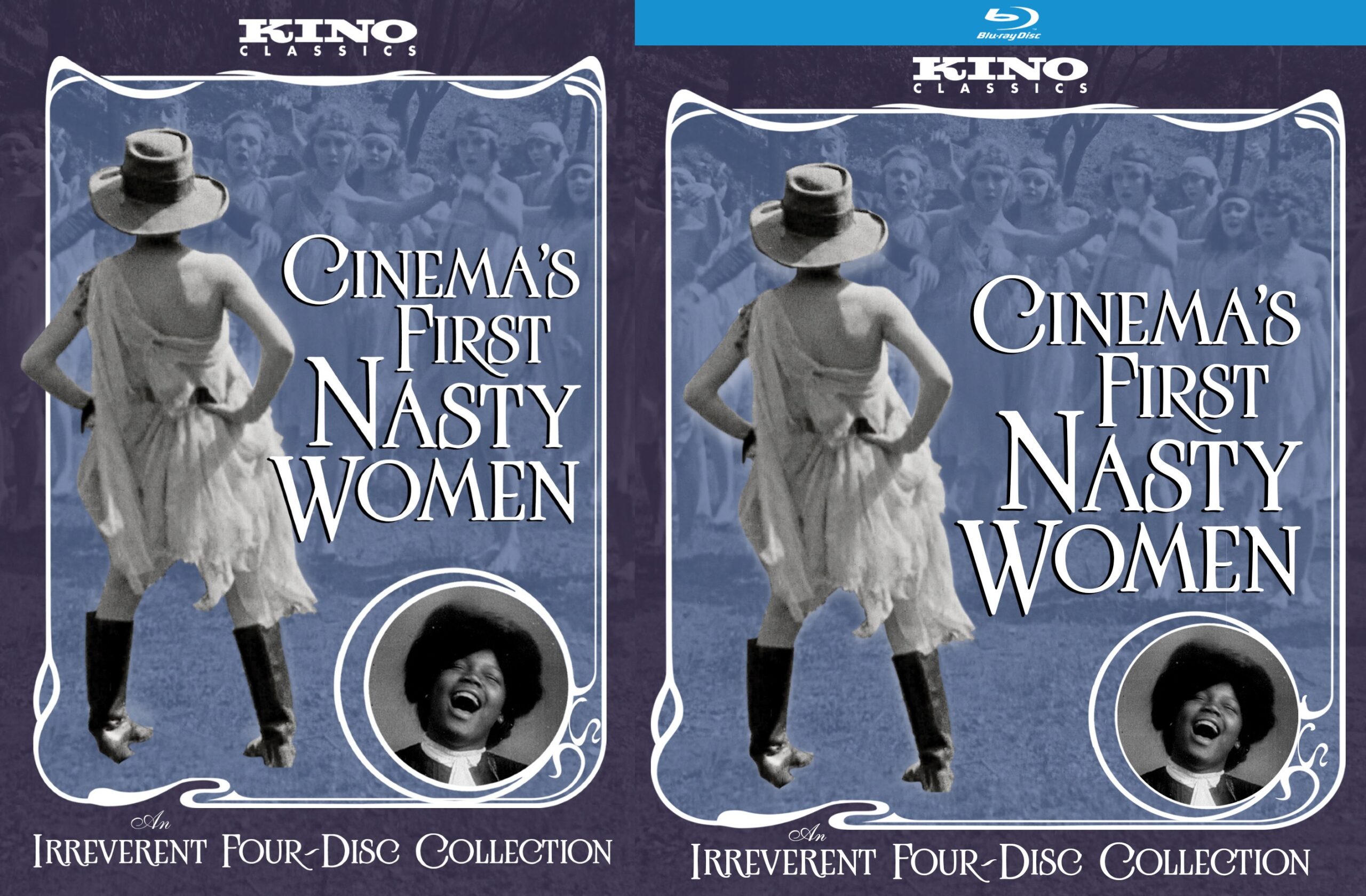

Cinema’s First Nasty Women presents a rambunctious roster of talented ladies from the silent era challenging gender norms from every direction. They turn households inside out; they invert class and racial hierarchies; they do everything that men do, and they do it all in high spirits. These women actors and characters, who are white, Indigenous, Asian, and African American, are brought together in a groundbreaking Kino Lorber box set of ninetynine films made between 1899 and 1926, constituting more than fourteen hours of running time. Based in equally significant scholarship by Maggie Hennefeld, author of Specters of Slapstick and Silent Film Comediennes (Columbia University Press, 2018) and Laura Horak, author of Girls Will Be Boys: Cross-Dressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema, 1908-1934 (Rutgers University Press, 2016), this collection remakes and expands the living history of the silent period. Hennefeld and Horak are the Project Directors, with archivist Elif Rongen-Kaynakcp from Amsterdam’s Eye Film Museum as cocurator.