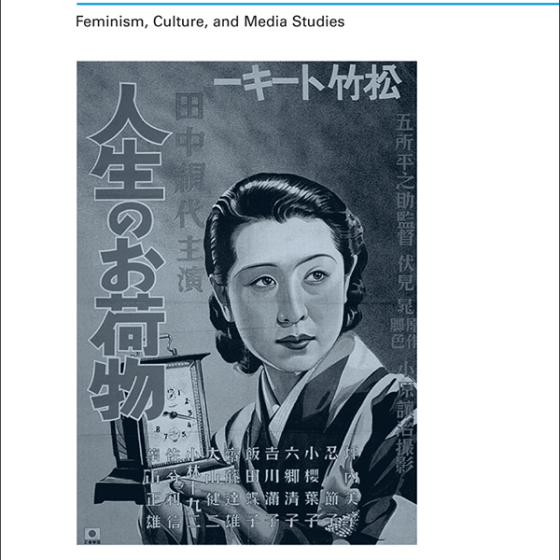

The Cinema of Naruse Mikio: Women and Japanese Modernity

Given the complex historical and critical issues surrounding Naruse’s cinema, a comprehensive study of the director demands an innovative and interdisciplinary approach. Russell draws on the critical reception of Naruse in Japan in addition to the cultural theories of Harry Harootunian, Miriam Hansen, and Walter Benjamin. She shows that Naruse’s movies were key texts of Japanese modernity, both in the ways that they portrayed the changing roles of Japanese women in the public sphere and in their depiction of an urban, industrialized, mass-media-saturated society.