Originally published in Cineaste XLVI No. 4 (Fall 2021).

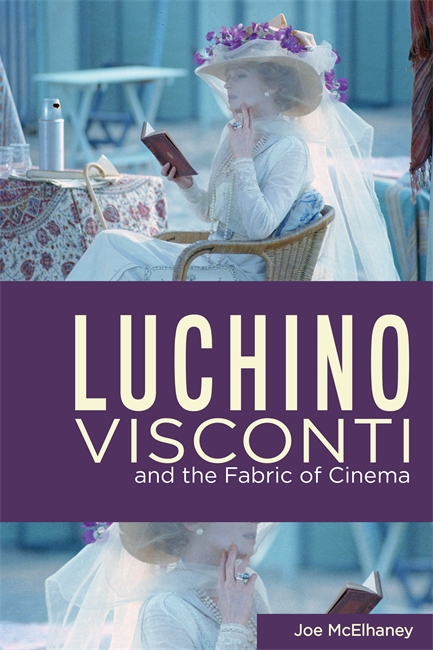

A cinema of fabric is a cinema that flows, flutters, and drapes; and it is also one that tears, tatters, and shreds. In Joe McElhaney’s elegant book on the cinema of Luchino Visconti, fabric serves as a multithreaded methodology with which the author explores a very distinctive set of films made between 1943 and 1976. Fabric in this account refers to the fabulous costumes and sets of Visconti’s period films, and also to the details of laundry, fashion, and decor of his neorealist films and late melodramas. The contradictions within the auteurist persona of the famous Marxist aristocrat becomes a productive tension in McElhaney’s unraveling of Visconti’s lingering attach ment to romanticism, and his veiled/unveiled identity as a gay man.

Visconti’s use of fabric in set design, costume, and as a kind of prop or fetish object is revealed to be an erotics of cinema, tied to both heterosexual and homosexual relationships. This may be particularly evident in a film such as

Death in Venice (1971), where Aschenbach (Dirk Bogarde) nervously watches the boy Tadzio (Björn Andresen) among the maze of softly waving canopies, towels, and veils of the beach scenes. Aschenbach’s tight collar and all the young men’s tight bathing suits are no less critical uses of fabric in the visual pursuit that structures the film. The final fluttering black fabric of the photographer’s tripod camera points to “a persistence in looking that is beyond the frame.” Another critical example is the gorgeous boudoir scene in Senso (1954) in which Franz (Farley Granger) is feminized by his handling of fabrics (not to mention his amazing white cape), while Livia (Alida Valli) seems to assume theatrical poses in her coy resistance. McElhaney deftly unpacks this scene to show how camera movements, conjoined with the lush display of tapestries, drapes, clothing, and bedclothes “enact a push and pull…between two divas.”